The

stone roofs of north-west Clare, Ireland. Sarah Halpin 2003

In 2003 Sarah Halpin studied the

history and staus of stone roofs in County Clare, Ireland, for a thesis

submitted to the School of Architecture University College Dublin as part

of a Masters in Urban and Building Conservation. The complete study based

on the thesis can be downloaded here. |

| The landscape of north-west Clare

is harsh and windswept. Wind-bent trees, dry-stone walls and low solidly-built

cottages characterise this part of Ireland. These characteristics have

evolved and been influenced by the local materials and conditions. One

of most enduring features of this landscape is the use of the local flagstone,

locally called Liscannor stone, used in farm walls, houses, paving, flooring

and on roofs. |

|

| The name Liscannor stone does not

relate to an individual quarry, it is used for a number of fissile sandstones

that have been worked in the area around the Cliffs of Moher and Liscannor

village. More specifically the stone is described as Moher, Luogh and Doonagore

slate, flag and flagstone after the quarries from which they are taken.

The genric name Liscannor probably arose because all these sources shipped

stone from Liscannor pier. It includes the current quarries at Luogh and

Moher, and in the past also included the now closed quarry at Doonagore.

Today Liscannor stone has come to describe any fissile sandstone that displays

the fossilised trails of marine activity such as that quarried at Moher

and Miltown Malbay. |

| In west and northwest Clare the

geology is dominated by shales and sandstones of Carboniferous, Namurian

age, previously known as the Upper Avonian Shale and Sandstones, Millstone

Grit and Flagstone Series with Coal in places, and the Coal Measures (Finch

et al pp74-75). In west Clare roofs of stone slates can be seen as

far north as Doolin to as far south as Kilrush. The stone is a hard siliceous

sandstone containing between 70% and 90% silica. Similar geological formations

occur in the north Kerry/west Limerick area, in the border areas of Carlow,

Kilkenny, Laois, Tipperary, and in County Leitrim and North Roscommon.

There appear to be no present day references to stone roofs surviving in

these areas. However, Wilkinson (1845) describes

the Carlow flags (although called Carlow flags they were actually quarried

at Kellymount and Shankhill in Kilkenny) as a 'thin bedded siliceous grit,

fine grained, dark grayish brown in colour, very hard and very durable;

the face of the bed is sufficiently smooth, and they do not require any

dressing….. Besides their use as flagging, they are much employed for roofs

and other coverings, where the weight is not objectionable' (Wilkinson

1845, 210-211). Although this 19th century reference mentions the local

sandstone being used as a roofing material, today there is only one stone

slated outbuilding known in the area. There is still a small number of

stone slated buildings, mostly out-buildings in County Leitrim and North

Roscommon. |

|

| At the Cliffs of Moher some of the

quarries are right on the cliff edge. It is the most well known of all

Liscannor stone types and is distinguished by the fossilised tracks

of molluscs, arthropods and worms which burrowed through the soft sand

and mud looking for food about 320 million years ago. This rock is currently

quarried at Derreen and Kineilty. More commonly, the stone's surfaces reflects

the conditions of deposition. Rippled surfaces indicate shallow water deposition

(as seen on sandy beaches) where wave effects penetrate, but smoother surfaces

indicate deeper water. In NW Clare the inland quarries of Doonagore produced

flags with dimpled or ripple marks, while the nearby quarries of Luogh

produced smooth flags. Colours vary from blue/black and grey/brown to more

russet tones. In the past a similar type of sandstone was quarried in and

around Ennistymon. The Ducks quarry south of Ennistymon also had the fossilised

traces of worm activity in some examples but was generally semi-smooth.

Its colour varies from brown to dark grey. Further south the stone was

also quarried at Moneypoint until the early 20th century and near Kilrush.

The sandstone with fossilised tracks of sea snails and wormswas also quarried

at Aylevarro near Cappagh. |

|

|

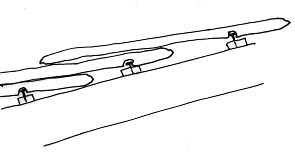

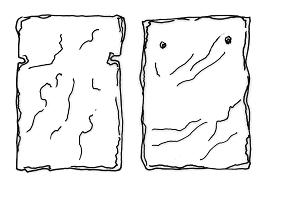

Slates for re-use.

|

|

|

|

Mohr slate showing the typical

fossilised animal tracks

|

|

| There is little information available

on the use of stone slates prior to the 19th century although there are

examples of thin stone in the walls of very ancient buildings. Donald Stewart

in his tour of Clare in 1788 'for the purposes of searching for and examining

Fossils, Ores and minerals' (Dillon) observed 'In

the Cliffs of the River Shannon, near Kilrush, are remarkably good and

large flags, with impression of almost every kind of animals, herb, etc.

..the flags are in beds, nearly horizontal, form one to six inches thick.'

At Liscannor stone slates were certainly being used at this time. Two examples

are Mohr House in Shingaunagh South townland west of Liscannor village

and Gliggrum House (now Sandfield House) in Ballyellery townland to the

north-east. The latter retained its stone roof until about 1995. |

| By the 19th century the use of stone

slates was well established. A Statistical Survey of the County of Clare

dating from 1808 by Hely Dutton of the Farming Society

described the dwellings of the better off farmers and other more well off

members of the population as having stone slate roofs: 'The better kind

of houses are slated either with a hard thin sandstone flag, procured in

the western part of the county, and near Lough Lickin' and that 'near Innistymon

thin flags are raised, which are used for covering houses; they do not

in general split into laminae thin enough, therefore require strong timbers

in the roof.' |

| First editon (1840) Ordnance Survey

maps show a number of quarries in the Liscannor area and to the SE of Doolin,

demonstrating that quarrying was already taking place before then. There

is no mention of quarrying in the Lahinch area, although there are a number

of quarries indicated further south near Milltown Malbay. |

| A study of valuation records around

the end of the 19th and early 20th century and second edition (1913) OS

maps show a boom in quarrying during the years 1890 to 1915. This was mainly

concentrated to the west and north of Liscannor in the townlands of Moher,

Caherbarnagh, Luogh South and Doonagore. This commercial quarrying was

carried out predominantly by a number of English Companies which came from

the Rossendale region

of Lancashire. This boom in quarrying lasted only about twenty years (1890-1910),

but with the onset of the First World War and the closing of markets the

companies eventually closed and left. These companies included the Liscannor

Quarry Company, United Stone Firms, Wm. Hampson & Co. Ltd. And Geo.

A. Watson & Co. Ltd. |

| G.O. Watson was one of the largest

companies operating at Doonagore with a quarry covering thirty acres at

three sites. Responding to the ready market for the stone they constructed

a three-mile 4ft 8-½ inch gauge steam tramway in 1903/05 which ran

until the company's demise in 1910/11. (Johnson

1997, 19 & 136). |

| The Geological Survey of Ireland

Industrial Mineral Records demonstrates that the quarrying industry did

not completely die out with the departure of the English Companies. The

tradition of local quarrying continued on though now concentrated in the

area to the NW of Liscannor, along the Cliffs of Moher and SE of Doolin. |

| In 1966, another Englishman with

experience of quarrying in Rossendale, Harold Phillipson opened a quarry.

He had previously worked with a blacksmith who had been employed in Watson’s

Quarry at Doonagore prior to the 1st World War. At that time there were

only a few local men working the quarries at Moher and Luogh. As there

was not much of a market for the sandstone at the time quarrying was not

a full time occupation, it was generally a sideline to the main occupation

of farming. |

| Harold Phillipson’s first quarry

works was situated near where the present Liscannor Stone Company headquarters

is in Luogh townland. This was at the time of rural electrification and

Phillipson paid £15,000 to be connected to the ESB. He employed locals

but work initially was very slow as there was very little building going

on but an order of stone for the Kennedy Memorial Park saved the company

from going under. Subsequently the market improved with orders for the

Rent an Irish Cottage Schemes and from the Office of Public Works. The

main demand was for flags for flooring, buildings stone and walls, but

not stone slates. In 1968, Roger Johnson joined him. The company developed

further with the help of small industries grants. Johnson later bought

the company in partnership with P.J. Ryan from Phillipson to form the present

Liscannor Stone Company. Today stone slates are quarried locally usually

from Luogh or Moher Slate. The slates are available in sizes from 1150mm

x 880mm to 450mm x 450mm with thickness varying between 13mm to 25mm -

½” to 1”. |

|

|

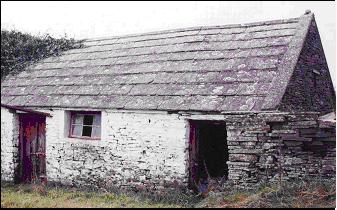

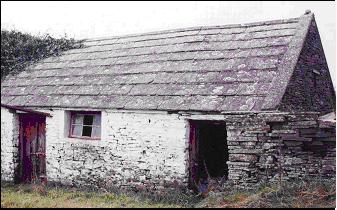

A Clare stone roof today

|

|

| Most buildings have simple gable

ended roofs with very little or no examples of hipped roofs, dormer windows,

or valleys. This paucity of roof types reflects the limitations imposed

by the large and somewhat cumbersome stone slates but also reflects the

simple vernacular architectural style. Given the immense roof weight many

roofs display solid timber trusses and purlins. Pitches of more than 40º

are generally not found. Rafter centers were generally in the region of

between 310mm to 380mm. In nearly all cases battens were attached directly

onto the rafters. There was only one example of roofing felt found. Stout

to more slender purlins were also sometimes used measuring between 185mm

and 150mm in section. Through purlins were generally used with one example

of butt purlins used. The wall thicknesses varied between 540mm to 755mm.

In all cases a ridge plank was used to form the apex. |

| The stone slates are randomly sized

laid to diminishing courses with the heavier and larger slates placed near

the eaves and the smaller ones near the ridge. Each successive course of

slates was chosen to provide adequate head and side lap over the previous

course of slates. According to local sources the traditional system was

to lay the battens to the size of the flag or slates coming out of the

quarry at that time. However, there was little information avaialable on

specific methods of slate laying employed, but it is likely that it was

similar to methods employed in England. |

| The average

head lap varied between 127mm and 203mm (between 5” and 8” on roof case

studies). This lap was larger than in the case of natural slate due to

the characteristic undulations of the sandstone especially found in the

Moher slate with its characteristic fossilised trails. Luogh slate due

to its smoother nature could be laid to a lesser lap. It was imperative

that a range of widths was available to the slater to allow sufficient

side laps otherwise slates would have to be cut to fit which in today’s

terms would be a waste of expensive slates and labour. |

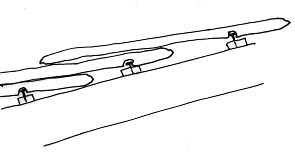

| The slates

were attached by iron nails through a double set of holes near the head

of the slate or via side notches (Fig. 8). The heavier and thicker slates

(known locally as flags) used on outbuildings were often just hung from

nails, which rested in notches picked out from the underside of the stone.

The stone slates used on outbuildings are known as flags due their immense

weight and size and could be up to 55mm (2”) thick. The immense size and

weight of the stone meant that as a rule they stayed insitu. Battens

were often not used so nails were hammered directly into rafters or purlins.

A house in Doolin, prior to its present Luogh slate roof, had an earlier

roof where the stone slates were attached to battens with bog deal pegs.

The pegs tapered to a point which were inserted into the battens to attach

the stone slates. |

|

|

On earlier roofs slates were

fixed with wooden pegs and later with two iron nails at the top corners

or at the sides (above) or hung from nails which rested in notches on the

slate's underside (below)

|

|

|

| According

to a local builder, recalling stone slate roofing that he saw carried out

in the 1950’s, the battens were laid as the work progressed because of

the randomly sized slates. If this is the case, it shows that already at

an early stage in the decline of stone slate roofing some of the traditional

skills were being lost. |

|

| The decline of these roof coverings

does not just result in the decline of individual roofs but also in the

loss of character of a street, a group of structures, an area and ultimately

a landscape. The material provides a sense of place and adds to the relationship

between the land and its people, thus making it a valuable feature of the

landscape. Elements of the landscape’s past history of use such as ringforts,

holy wells and old field systems are already protected, so is it too much

to ask that this characteristic element be protected and retained as well? |

|

Finch, T. F.,

Culleton, E. & Diamond, S. 1971 The Soils of County Clare. Dublin.

An Foras Talúntais (The Agricultural Institute).

Dillon K.,

1953 Donal Stewart and the Mineral Survey of Ireland in North Munster Antiquarian

Journal Vol. VI. No. 5.

Dutton, H.

1808 Statistical Survey of the County of Clare; with observations drawn

up for the consideration of the Dublin Society. Dublin. Graisberry &

Campbell.

Johnson, S.

1997 Johnson’s Atlas & Gazetteer of the Railways of Ireland.

England. Midlands Publications Ltd.

Wilkinson,

G. 1845 Practical Geology and Ancient Architecture of Ireland. London. |