RE-ROOFING PITCHFORD CHURCH

26/ 04/13

Re-roofing Pitchford Church

Chris Wood

English Heritage Building Conservation and Research Team

The grant aided recovering of the roof at St Michael’s and All Saints church, Pitchford, near Shrewsbury required special Harnage slates. Here Chris Wood describes the work and lessons learned.

The nave roof of St Michael’s and All Saints church, Pitchford, near Shrewsbury has been recovered in the local Harnage stone slates after a new quarry was opened to provide a supply of this rare material. The work was the culmination of four years of effort, which included finding a source of new stone, obtaining planning permission to open the quarry, and finding an operator to quarry the stone and produce the slates. The project also required a detailed survey of the old roof to see why it failed and to help design the details of the new roof.

This article was originally published in 1999 in English Heritage Conservation Bulletin 36. It is reproduced here with English Heritage’s permission.

Harnage stone revived

This is thought to be the first time that Harnage stone had been quarried for more than 60 years. Commercial production ceased more than a century ago. The stone was once actively exploited for roofing, but with cheaper imports of Welsh slates and clay tiles it rapidly fell out of production and there are only a few more than 20 buildings still clad in this unique and distinctive material. There is nothing quite like this stone anywhere else in the UK, for Harnage slate is actually a shelly or calcareous sandstone, which splits quite easily, and gives a variety of different thicknesses. The lack of supply of new local material is a problem in many regions in England, where stone roofs are being repaired with different products imported from other parts of the UK or from abroad. Worse still is the fact that roofs are regularly cannibalised (sometimes stolen!) to provide a supply of second-hand material. English Heritage were keen to see St Michael’s repaired in Harnage stone as their Roofs of England campaign was actively trying to help rejuvenate local stone slate industries. A great deal of information has been learned from the Pitchford story, which it is hoped will be useful in other areas.

History of the church

St Michael’s is a Grade I listed church, and lies some 50 metres from another Grade I building, Pitchford Hall, which is also roofed in Harnage stone. Lack of new material resulted in recent repairs to the Hall being carried out in a variety of different stone slates. The church retains much of its original twelfth-century fabric despite being altered over the centuries. It is not known if the original church roof was clad in Harnage stone; the first written mention of Harnage slates occurs in the mid fourteenth century but it is likely that this prestigious building would have retained its stone slates, at least while there was a supply of new material.

Earlier this century the chancel roof was repaired in plain clay tiles. In the 1930s the nave roof was stripped and some of the old Harnage slates were redressed and reused, but the bulk was quarried from Acton Burnell Estate nearby. Correspondence at the time describes this as slow and ‘painfully costly’, as the beds of stone lay in awkward positions and a great deal of overburden had to be moved (Link). The mounting costs dispelled hopes of replacing the tiles on the chancel with stone. Good quality local oak was used for cleft laths, pegs, and new rafters. Unfortunately, the reslated nave roof, which should have lasted at least a century, started to leak after little more than 50 years and it was clear from the outside that many slates were no longer held onto the laths.

By the 1990s, the Parochial Church Council (PCC) was faced with the expense of reroofing in a material that had apparently failed prematurely and, not surprisingly, there was pressure to replace the whole of the nave roof with machine made tiles to match the chancel. English Heritage agreed that the works would be eligible for grant aid provided that this was done in Harnage stone. If it proved impossible to produce the new stone then it was agreed they would not oppose the use of tiles.

Finding the quarry

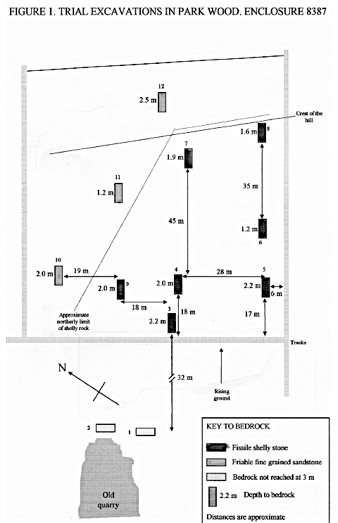

English Heritage commissioned its consultant Terry Hughes, who had been leading the campaign, to investigate all the potential sources of Harnage stone and carry out a feasibility study to assess potential demand. Together with David Jefferson (consultant geologist) they identified 16 former quarry sites, later narrowed down to two. Consent from the landowners was obtained for excavating trial holes a few metres in depth and samples of rock were taken for analysis and testing to make sure that they would split satisfactorily. The selected site at Park Wood on the Acton Burnell Estate had a number of advantages. Not only was there an adequate supply of fissile (easily split) stone at reasonable depth, but the site was also on a hill hidden by trees. The comparatively small scale of the operation meant that the occasional vehicle movements would have little impact on the local roads and villages. These were important considerations for the County Council’s minerals planners, who had to balance the needs of the built environment (historic buildings) with those of the natural environment. The fact that the contractor who would win the stone planned to remove the rock and dress the slates at his works in Wiltshire was also beneficial, as it reduced the amount of noise and general activity at the quarry. It also reduced production costs.

The planning permission stipulated times of working, but the Acton Burnell Estate also required the quarrying to end by October because the land provided valuable pheasant covers and the lucrative shooting season was scheduled to start in November.

Winning stone and dressing it

Taking the decision to open the quarry was complicated. English Heritage would be grant aiding most of the costs, but it was still the PCC, through its new architects, Arrol & Snell Ltd, who would issue instructions. Everyone had to be satisfied that sufficient funds were budgeted to complete the job. The problem was, that there were a large number of uncertainties. For example it was not known exactly how much stone was needed for the new roof. Reasonable estimates could be made, based on the average weight of slates found at the church. How much of the old could be reused and how much new was needed, would not be known until the roof was actually stripped and individual slates inspected. Most worrying was the possibility, albeit remote, that the quality and quantity of new material expected following the trial excavations might not live up to expectations, or that the wastage would be far greater than anticipated.

In order to move the project forward English Heritage accepted that they would have to be directly involved in the production of materials, so the amount of grant was increased to cover the ‘worst case’ estimates, and it was assumed that new stone would be required for the whole roof. Any unused new slates would become theirs for use on other buildings. Getting this procedure in place meant a delay, but fortunately all parties reacted quickly and the instruction was issued to The Completely Stoned Company to begin quarrying in October. Unfortunately, Shropshire experienced the wettest October since records began in 1841 and the site became almost inaccessible to vehicles. The minerals planners, however, were understanding and accepted a different phasing of the work. Even the pheasants quickly grew accustomed to their new neighbours, so the Estate was happy to allow quarrying to continue into November.

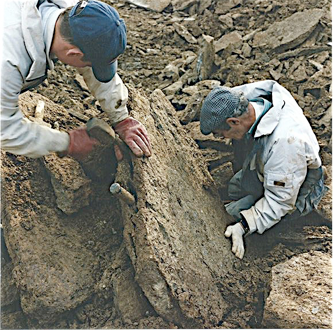

Although at its peak three excavators were used, most of the work was still done by hand. Indeed hand shovels were used to expose the first area of good fissile stone, which, ominously, was some four metres below ground. As quarrying moved up the hill, however production improved, and on average five tonnes of stone were produced per day. As the rock splits best when wet, it was initially split and roughly dressed and kept wet until dispatched. When frost threatened the stone was covered with polythene. The quarrying was successful, with far less wastage than expected, and plenty of large slates were produced, which the survey later showed proved to be critical.

Moving the slates took longer than expected because the rains had turned the steep access track into a quagmire. Nonetheless, the instruction to stop work was given at the end of November, when enough stone had been won to cover the whole nave roof. Work continued in order to win enough stone to complete the reroofing of Pitchford Hall. Once the stone arrived at the contractor’s works in Wiltshire it was roughly cut to size with a mechanical saw and then hand dressed to provide the traditional finish. The final cost of the stone was £640 per ton, which came midway between the highest and lowest estimates.

Investigating the failed roof and designing the new roof

Terry Hughes carried out a thorough survey of the nave roof to find out why it had failed. This required the erection of scaffolding inside and outside the church and a two metre strip of slates was removed from each side. Every course was measured and recorded. The slates were generally in good condition and it was expected that most of them could be reused; but the survey revealed that most of the oak pegs and many of the laths had completely rotted. This was mainly owing to the excessive amount of mortar bedding that had trapped water and restricted ventilation. This had in turn encouraged the growth of plants, especially ferns, whose roots filled the space between slates and added to the dampness of the roof. Small slates too low down on the roof (80% were 12 inches long or less) meant that there was an insufficient overlap of slates to keep water out.

Various approaches were considered for the new roof, including a return to the traditional method of hanging the slates by oak pegs on split laths. Because of a number of complications, however, it was decided that the roof would be gap-boarded even though this reduced the flexibility for setting out the random courses of slate, because the nails could coincide with the gaps. The slates were nailed through two layers of felt over the boards and directly over a ventilated rafter space. (A full description of the works appears in English Heritage Research Transactions Vol 9. Stone Roofing).

Much has been learned about the issue of opening a new quarry to supply stone slate and more quarries will need to be reopened if these distinctive and important features of our heritage are to be retained. The cost of stone roofing is expensive, but it must be remembered that a properly designed roof should last at least a century and most of the slates should be capable of reuse. It is also one of the most sustainable of materials and uses little energy to produce.

St Michael’s church has acquired a new stone roof using the same materials that have most likely adorned the building for many centuries. Reroofing the chancel roof in stone was also considered but dismissed because the present roof functions well. Now that a source of slates has been established it should mean that buildings roofed in Harnage stone can be repaired without having to import different stone or to cannibalise another building. Perhaps in the future we might see the roofs of some important buildings, which have lost their Harnage slates over the years, again display this unique material.

Subsequently to roofing of the church some of the extra slates were used to for repairs of two other roofs. There are only 22 buildings known to have Harnage roofs.

The state of the nave roof before repairs began

Splitting stone in the delve

Trial digs in Park Wood above the 1930s quarry

Rivings stacked for transport

A two metre strip was removed to record the constructional details

Promising material dug at Park Wood

The 1930s quarry

Stone slate produced during the trial digs

The full extent of the delving

Slating in progress

Finished roof

Finished roof

Pitchford church before work started