THE APPEARANCE OF STONE SLATES

The appearance of new stone slates is influenced by grain size, colour, surface features and mineral composition.

Because the environments and processes of deposition of rocks varied over quite short distances and altered in time, their composition and structure can alter significantly even within a quarry. Therefore, it is quite possible that quarries would have produced stones which varied in these aspects from time to time. It follows that it may not be possible to predict the continued production, nor to insist on the supply, of products with particular characteristics except at the coarsest level of discrimination.

Despite this the following characteristics are useful when trying to identify a stone slate and for any that are important to the appearance of a roof they can be included in a draft specification and agreed or revised with the supplier.

After installation the roof’s appearance can be modified by pollution or plant growth.

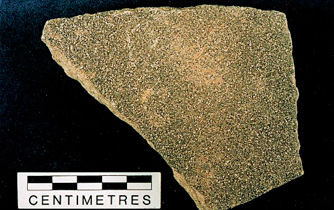

Grain size

For hand specimens, grain size is expressed on the Wentworth scale where the following dimensions apply:

-

-very fine 0.063 - 0.125 mm

-

-fine 0.125 - 0.25 mm

-

-medium 0.25 - 0.5 mm

-

-coarse 0.5 - 1.0 mm

With practice and a magnifying glass these classes can be quite easily distinguished in the hand.

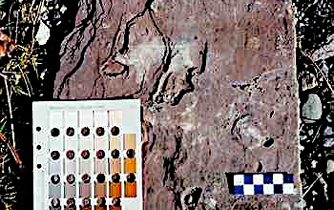

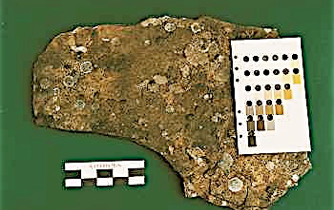

Harnage stone with brachiopod shells

Fine grained Carboniferous sandstone

Colour

Colour is a consequence of a range of factors and their effect on the stone's minerals. These include, the nature of the original sediment, the depositional and post-depositional environment and, following installation on the roof, weathering, pollution and plant growth. It is important therefore to always use freshly exposed rock when comparing colours. Description of this feature can be standardised by the use of Munsell Colour Charts.

It’s usually helpful to define a range of colours covering the stone’s variations. For this reason it is wise to avoid over-precise specifications of colour especially in the range yellow - buff - brown, all of which can appear in a single stone.

Sandstones normally look more or less black on old buildings and this may be due to industrial pollution or, possibly, algal growth. Limestones often turn grey within a few years of installation.

Many stones especially from near surface deposits will have been stained by iron-bearing water flowing through cracks in the rock. These colours are usually permanent and are often known as rustics.

Cotswold limestone

Devonian stone Herefordshire

Surface features

At the two extremes of this characteristic are the flat featureless Grey Slates typical of Yorkshire and Lancashire and the highly textured and rippled rocks from Ham Hill in Somerset and Freebirch in Derbyshire. The latter may show chisel marks where the worst of the ripples have been dressed off to enable them to lie flat on the roof. In between these extremes there are examples of granular texture, stepped beds, and worm burrows and other animal generated features either in positive or negative cast.

Highly textured Freebirch stone, Derbyshire

Ham Hill stone smoothed by dressing with a bolster

Edge dressing

This is a very important aspect of stone roofing and one that is often done badly by quarries. The methods vary each producing regional features. Sawing a slate square before dressing is acceptable provided the edges are then dressed properly.

Collyweston and Cotswolds slates are struck straight onto the edges producing a double bevel. Traditionally when done without pre-sawing this produced a slightly wavy edge but ore-sawing tends to make them very straight which looks un-natural.

Most sandstones are struck onto the slate’s face with a sharp edge similar to a brick hammer. Striking into the edge with a brick hammer or an axe leaves a partly sawn edge and will / should be rejected by conservation officers.

Collyweston slate

Correct dressing of Hereford stone slates

7/3/13

Minerals

Surface mica significantly modifies the basic sandstone appearance imparting a distinct grey colour. However this feature may be short lived once exposed on a roof.

Indirectly the presence of carbonate may be determined by the predominance of grey lichen growth as against the greens and yellows which are more characteristic of non-calcareous stones.

Organic layers usually look brown or black and are generally only found in the Westphalian (Coal Measures) sources. They rarely appear on the surface of new tilestones and therefore do not affect their appearance but they can reduce the durability of the product.

Surface mica will quickly erode revealing the stone’s true colour

Size range and mix

Different stones produce slates of different sizes. The Carboniferous sandstones are often big, ranging from as much as 48 inches down to maybe no smaller than 18 inches; Cotswold stone slates might be as small as 6 inches. Within regional types and even within quarries there would be variations of size ranges. These are important influences on the appearance of roofs and on a national scale resulted in distinctive regional roof styles. For re-roofing it is normal to try to conserve the size mix but it must be remembered that the natural mix from a quarry may also have varied with time so it may not be realistic to impose too tight a specification on the sizes to be supplied. The fact is that stone slates were always sold 'as found' and it was the slater's job to turn them into a roof. This still applies today and if the rock and the quarry have moved on then so should the roof.

Large sandstone

Roofs should always use the quarry’s natural size mix

Generic stone slates

Within a region it is all too easy to assume that there is only one stone slate type. In the South Pennine study a collection of slates were analysed using the characteristics described above to try to distinguish how many generic types would reasonably satisfy conservation objectives. Surface features are considered to be the most important, followed by colour and grain size in so far as it determines texture. Superficial minerals may influence the appearance when new but the processes of weathering and particulate pollution will rapidly modify this feature and the inherent colour. Size and size range are not included as generic features although future work may show this to be an appropriate feature to include in a generic description.

The following generic types were proposed:

-

-Yorkstone: Flat, featureless, without substantial stepped bedding, fine to medium grained, buff to dark brown.

-

-Kerridge: Flat, featureless, without stepped bedding, fine grained, gray mica surface.

-

-Cracken Edge: Textured, with or without stepped bedding, fine to coarse grained, white and buff to dark brown.

-

-Teggs Nose: Textured, with or without stepped bedding, fine to medium grained, pink.

-

-Freebirch: Strongly textured or ripple etc marked, fine to medium grained, buff to dark brown and olive to gray.

-

-Whitwell: Strongly textured or ripple etc marked, fine grained, gray or pink, Magnesian Limestone.

Inevitably these types are a compromise, it is always possible to further subdivide. However it was considered that they represent a reasonable basis on which to promote production of stone slates within the region. Other regions would benefit from a similar analysis.

Plants

Plants such as lichens will change the appearance of the stone slates after a few years. This is important and they should not be removed. Imitation stone slates do not support the same plants as natural stone and are therefore not good reproductions of traditional roofs. Cement based imitations tend to become covered in thick black moss.

Excessive plant growth does need to be removed periodically but this should be done very carefully to avoid damage.

Limestones and sandstones support a wide variety of lichens

Iron stained Pennant sandstone

Excessive moss should be carefully removed

Wrong way to dress sandstones

David Ellis in an excerpt from the English Heritage video of Collyweston slating

Tony Muhl dressing a Hereford sandstone

Dave Cater dressing a Cotswold stone tile

Correctly dressed Hereford stone slates

Choosing the right stone or slate for roof conservation

Appropriate material

1 The original stone or slate. If unavailable, can it be specially made (see Pitchford Church). If not then -

2 The nearest geologically similar. Do not replace stone with metamorphic slate or vice versa.

3 If there is no geologically similar option then consider whether a geographical near neighbour might be acceptable. This will probably involve a significant change of appearance to the roof so should only be adopted if all else fails.

4 Never use fake (concrete, plastic etc) products on listed buildings.

Appropriate format

1 The primary options will be whether the original roof is random sized or single sized (tally) slates. If the original roof is stone it will be random sized.

2 Random roofs should always be renewed as random.

3 Random sizes should be exactly that. Not a mixture of a small selection of single sizes.

4 Random metamorphic slates are not an appropriate substitute for stone (or vice versa). It will be too large and change of appearance. There will almost certainly be a more suitable stone option.

Setting out the roof - lath or batten gauges

There are many was to set out slates in diminishing lengths. The system adopted for re-slating should be based on a detailed examination of the existing roof. Photographs of the slating before it is stripped will provide little useful information. Slate lengths, head laps and their lath gauges need to be recorded for a full understanding. Photographs of slates stripped diagonally over several courses will be useful (see Recording a roof).

The other important aspect for conservation is the original detailing. This is especially important for vernacular valleys which were usually constructed without lead and therefore are dependent on accurate arrangement of the slates and the appropriate (original) gauging system to be successful.