CAST IRON ROOF TILES

Cast iron tiles in Spreyton Devon

09/02/15

PATENT CAST IRON ROOF TILES 1897

The six drawings in Carter’s patent

Devon may not be generally regarded as a stronghold of early iron construction. However it has some choice examples to offer, and also has some territorial claim to a novel form of iron roof covering invented in 1827 . On 8 December that year Elias Carter, describing himself as an 'upholsterer of Exeter', was granted a patent, No 5552, for 'Covering for the Roofs of Houses and other Buildings'.

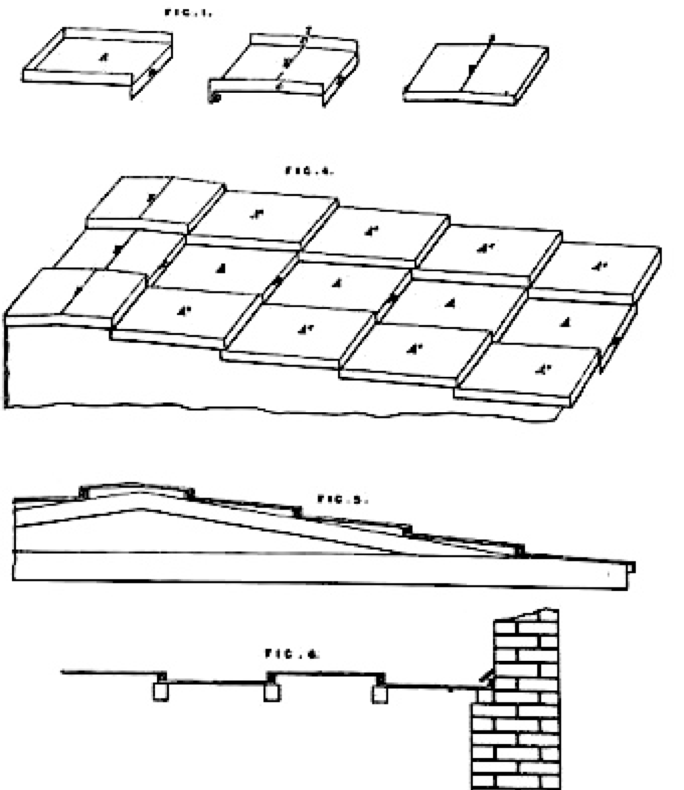

His invention consisted of: 'particular shaped plates of iron or other suitable metal or materials to be used in a regular series...'. Although the patent did not claim any particular metal or material, or any particular dimensions, Carter recommended cast iron plates, three sixteenths of an inch thick and two feet square, the sides and lips two inches deep. Accompanying drawings in the relevant volume of patents in the Science Reference Library show the tiles.

There were three types. Type 'A' was constructed like a shallow tray with the lip on one side turned down. Those covering the main pitches of the roof were simply laid with the downturned lip hooked over the upturned lip of the tile below. The ridge consisted of two different designs of tile, the 'low ridge plate', as Carter described it, with two down-turned lips, hooking over the tiles on either side of the ridge and two upturned lips. These accommodated the 'high ridge plate or cap plate', where all four lips were turned down. The roof covering, as Carter describes it, was laid in vertical courses, rather than the horizontal system used for laying courses of slate. Carter did not specify or recommend the form of the trusses to carry his roof covering system, neither did he make any claims for the roof as being fire-proof.

Carter's tiles were an invention that did not merely gather dust in the patent office. The Exeter Flying Post, 9 January 1833, reports that they were used to cover the roof of the classical St Leonard's church in Exeter, built to the designs ofAndrew Patey and consecrated 2 January 1833. The church, which replaced a two cell medieval church on the site, had a west end portico (Fig. 2).

St Leonard’s Church Exeter

Patey did not design cast iron trusses for St Leonard's, but a bolted timber roof to receive the 'iron plates', as the tiles are described in the 1831 articles of agreement with William and Henry Hooper, builders and carpenters (DRO 1862 A/PW 51). St Leonard's was extended to the west ten years after it had been built (Exeter Flying Post, 27:07:1843) to the designs of Charles Hedgeland. The extension was roofed with Delabole Duchess slates on boards, but the, iron plates were retained on the earlier part of the building (DRO 1862 A/PW 54). Presumably Carter's tiles survived until the classical church was replaced in 1867 by the existing Gothic Revival St Leonard's to the designs of S. Robinson. This was extended by Robert Medley Fulford in 1883.

CARTER’S IRON TILED ROOFS

St John the Baptist Church Broadclyst Devon

Carter's tiles were also used on Broadclyst parish church in 1832-1833. The church was given a new roof in a general restoration project carried out by Mr William Wills, builder of Exeter, under the direction of Sir Thomas Dyke Acland (Exeter Flying Post, 7:03:1833 & 24:04:1834). The remains of the tiles are known as heaps of rust found in the roof space by the quinquennial architect. The Pevsner entry on Broadclyst mentions iron fire-proof trusses from the 1830s scheme, but the Flying Post refers to 'Carter's Patent Roofing'.

Extract from an original article by Jo Cox Keystone Historic Buildings Consultants

First published in Devon Buildings Group Research Papers vol 2 2006

St John’s Church Broadclyst

Gloucester County Lunatic Asylum

St Paul’s Church Honiton

Old Vicarage Spreyton Devon

The Vicarage yard includes a very intact single-storey rear wing, early 1830s in all its details (Fig. 10). The wing has a very shallow pitched roof. This allows, above its roofline, two first floor windows in the main block. The roof is covered with Carter's tiles with a patent stamp of 1827 and a foundry stamp of 'Toll End'. The tiles were suffering from rust along the right angle of each lip.

The owner of the house established that Toll End is near Bromsgrove. Further research by Peter Child, who contacted the Black Country Living Museum, located it precisely in the Tipton Area, near Dudley. Louise Troman, the curator, has identified a firm called the Toll End Ironworks, shown on an 1870 map as working alongside the Horseley Iron Works:

Gloucester County Lunatic Asylum

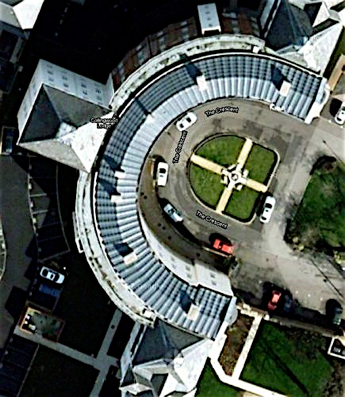

This opened for patients in 1823, but suffered a serious fire in 1832. The fire was thought to have been caused by the flue of a wash-house boiler, 30 feet away from the main building. Burning soot from the flue was suspected to have caught fire and landed on the roof of the crescent portion of the hospital ,and from thence under the Slates' (Gloucester RO, H022lll1). The crescent was the show front of the hospital and, in a system which segregated patients according to class as well as illness type, accommodated the 'opulent' patients, who paid for their own keep. Their fees helped to subsidise 'second-class' patients, who were housed in the wings off the ends of the Crescent. The 1832 fire, immune to class distinction, also spread to a section of the rear pauper lunatic wing, where it abutted the rear of the crescent in the centre.

St Paul’s Church Honiton Devon

Searching around for other likely candidates for Carter's tiles, John Allen of the Royal Albert Memorial Museum suggested that they might have been used by Charles Fowler at St Paul's, Honiton, completely rebuilt in 1835-1838. Fowler, born in Devon and best-known as the architect of Covent Garden Market, designed an experimental iron roof as part of the comprehensive rebuilding of St Paul's, as well as using hollow cast iron columns for support. The rebuilt church was designed in a Romanesque Revival style. The roof was clearly rather more ingenious than the application of a cast iron covering, either to conventional timber or cast iron trusses. It post-dates the remarkably sophisticated cast and wrought iron roofs (slate-covered), fabricated by the Horseley company, to three of John Rennie Junior's gigantic victualling buildings at the Royal William Victualling Yard, Stonehouse, Plymouth 1827-1834.

The specification to the rough mason and bricklayer required the construction of spherical vaulting over the apsidal chancel with flints and concrete, well consolidated 'and carefully formed to the exterior curvature by moulds, also having a circular cavity'. The exterior of the chancel vault was to be 'well-covered with cement' and had no other external skin. The other roofs required ' a course of slate to be laid upon the iron ribs to receive the tiling equal to the width of the ribs ...'. There is no specification to a tiler and no reference to the tiles being cast iron.

The Devon evidence to date might suggest that Carter's patent for iron tiles was yet another well-intentioned but impractical 19th century invention. The account of St Leonard's church in the Exeter Flying Post in 1831, which describes Carter's system as 'generally adopted and admired in the Metropolis’ (26:05:1831), could be dismissed as an extravagant puff for a local man. However, there are two examples, known to the author, of Carter’s patent tiles in situ, surviving from the c. early 1830s. These represent a roof covering which has had a lifespan of 165 years, a remarkable example of durability. The first Carter example is the Gloucester County Lunatic Asylum.

Fire-prevention was always a consideration in a lunatic asylum. It was not just that some patients had tendencies to arson, but the scale of early heating, washing and cooking systems in a large institutional complex presented fire risks. As the damage in this case was considered to have been from above, it was not surprising that a roof covering judged to be fire-proof was chosen for the repair. The fire-damaged portions of the slate roof - the whole of the crescent and part of the pauper lunatic wing - were replaced with Carter's patent roof tiles, which are stamped 1827, the date of the patent.

In 1856 the crescent portion of the Gloucester hospital was widened to the rear. The new work retained the cast iron tiles on the original width of the building, but did not extend them over the new work, which was roofed separately. In 1858 the hospital suffered another fire, this time in the north wing off the Crescent. The fact that the Crescent was saved, in spite of having had smoke issuing from the roof of the central part, was put down to the 1832 'fire-proof' cast iron roof. Seen from above, the roof covering has a rugged, large-textured appearance, resulting from the different planes of the alternate vertical courses of tiles.

Although the author has only seen Carter's tiles at Gloucester through holes in the ceiling of the hospital and from aerial photographs, a close inspection for the regional health authority, carried out in 1987, described the roof construction supporting the tiles and the general condition of the roof at that date (Roofing survey by Posford, Pavry and Partners for the District and Capital estates Department of the Gloucester Health Authority, February 1987). In the crescent 'Purlin bars' are supported on cast iron tied rafters with a central hanger rod. The timber and cast iron elements of the roof were described as in good condition in 1987, as were the tiles, with some evidence of corrosion at the joints and gutter line, the undersides of the tiles retaining their original paint protection. Over the pauper lunatic wing the purlin bars are supported on timber, not cast iron rafters. However, the report declared that the condition of the tiles and timber construction over the pauper wing was as good as over the Crescent.

'In 1827 there was a firm called the Toll End Furnaces Co., later called the Toll End Company and this, I believe was either an earlier part of the Toll End Ironworks or a sister company who were pig iron producers as opposed to producers of cast iron goods. Certainly in 1839 they were averaging 54 tons of pig iron a week, and it was likely that the related ironworks was casting such goods as graveslabs, firebacks and later cooking utensils and decorative architectural work' (letter to Peter Child, S November, 1999).

The large scale of the tiles on a small and relatively low building at Spreyton results in a slightly odd appearance at the eaves where the staggered edge of the vertical courses of tiles is revealed. There is slate flashing at the junction with the main block of the house, which was evidently no simple task to construct.

Quite why Carter's tiles should have been used at Spreyton in rural mid Devon remains a mystery. It seems odd that a simple service block should have received so much architectural attention, quite apart from a novel form of roof covering brought from a distance and which must have been a heavy load to transport. The vicar may have heard about the tiles through their use on the Broadclyst and Exeter Churches.

It seems very likely that a roofing system that has succeeded so well at Gloucester and Spreyton was used on other buildings. The possible link with Charles Fowler may be a red herring but the Exeter Flying Post's reference to the use of Carter's tiles in London is, in the author's opinion, probably no exaggeration. While Devon remains a good candidate for further evidence, whether documentary or in situ, of Carter's tiles, there may be surviving examples in London or elsewhere, given manufacture in the Dudley area. The date range 1827 - cl845 seems to be the most promising one. Likely buildings are not only those where fire-proofing was an issue, but also where relatively flat pitched roofs were wanted. Iron tiles are known on the roof of the Palace of Westminster, still in situ, but these are not Carter's tiles and are fixed with nibs, in the manner of clay tiles'

The Palace of Westminster cast iron roof

The Old Vicarage Spreyton (see also top of page)

Jo Cox would be very interested to hear of any examples of iron tiles whether in Devon or in other parts of the country.