THE TAXONOMY OF SLATING

16/5/13

Slate and stone roofs can be classified in two ways. By the materials they are made of and the way they keep out rain. The latter is explained here.

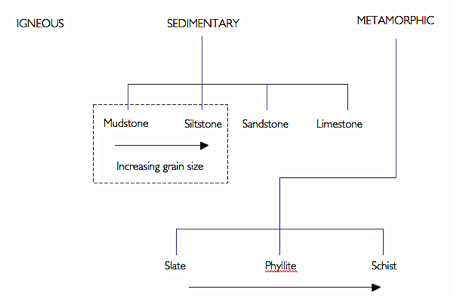

MATERIALS

They are

-

-igneous

-

-sedimentary

-

-shale (naturally fissile mudstone)

-

-mudstone

-

-siltstone

-

-sandstones

-

-limestones

-

-metamorphic

-

-slate

-

-phyllite

-

-schist

SLATE AND STONE ROOFS

SANDSTONES are formed from lithified sediments(sands)most commonly deposited subaqueously (rivers, lakes and the sea), but they can also be formed in arid environments such as deserts. These environments can include -

Terrestrial

-

-Rivers

-

-Alluvial fans

-

-Glacial outwash

-

-Lakes

-

-Deserts

Marine

-

-Deltas

-

-Beach and shore faces

-

-Tidal flats

-

-Offshore bars and sand waves

-

-Storm deposits

-

-Turbidites (deep-water submarine channel and fan deposits)

See here for more information

The sediments vary in grain size from 0.06 to 2 mm and are bound together with a variety of ‘natural cements’. The most common are silicates such as quartz or carbonates like calcite but also include hematite, limonite, feldspars, anhydrite, gypsum, barite and clay minerals, and zeolite minerals. Some sandstones composed of coarse, angular grains are commonly known as gritstones.

In the UK the largest source of sandstone roofing is the Carboniferous successions of the Pennines. These fall into two groups the Namurian and the Pennine Coal Measures of Lower Westphalian age.

Other important sandstone roofing sources in the British Isles and Ireland include those cropping out in:

-

-Bristol and the South Wales Coalfield (Carboniferous);

-

-in an area from Llandeilo in South Wales to Ludlow, Shropshire (Silurian - Pridoli);

-

-Horsham in Sussex (Lower Creataceous, Wealden Group);

-

-Welsh Marches (Ordovician and Devonian, Old Red Sandstone);

-

-Lancashire and Cumbria (Carboniferous);

-

-Eden Valley Cumbria (Permian)

-

-Lanarkshire Coalfield; (Carboniferous);

-

-Tayside, Caithness, Orkney and Shetland (Devonian Old Red Sandstone);

-

-County Clare (Carboniferous).

See also Introduction to stone-slate geology

LIMESTONES are formed by a variety of sedimentary and chemical processes. Those used for roofing are composed of grains of, for example, quartz sand or shell debris, in a fine-grained matrix and a natural cement which binds these framework grains together.

In the UK limestone roofing is mainly produced from the Lower, Middle and Upper Jurassic and from the Magnesian Limestone of Permian age (see Introduction to stone-slate geology). The Middle Jurassic is the most extensively worked interval but other important sources also include Lower Jurassic Lias limestone at Ham Hill in Somerset and Chacombe near Banbury, and the Upper Jurassic at Purbeck in Dorset. There are records of other Lias rocks being worked for roofing at Queen Camel in Somerset; near Tewksbury, Gloucestershire and at Burley Dam in Cheshire but there are no known surviving examples of roofs, indicating that the trial production or the slates themselves were unsuccessful. However, Lias roof slates have been found on a Roman site in Somerset.

Middle Jurassic roofing stone has been produced in Dorset, Somerset, Wiltshire, Gloucestershire, Oxfordshire, Northamptonshire, Lincolnshire and North Yorkshire. Well known examples include Forest Marble, Taynton Stone, Fullers Earth Rock, Stonesfield Slate and Collyweston Slate.

MUDSTONES AND SILTSTONES are very fine grained sedimentary rocks which are the principle sources of sedimentary roofing stone. They are not metamorphosed but split easily along natural bedding planes and can look like true slate. They have often been imported and sold for roofing in recent years. Unfortunately these thinly split stones do not always have the properties of slate and can fail on the roof in just a few months. In contrast some more thickly split examples such as those used for roofing in Orkney can have a very long life.

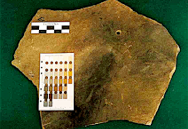

Permian age red sandstone from a dune environment

Jurassic limestone

Cambrian slate - conifer green from Penrhyn quarry Wales

Norwegian schist

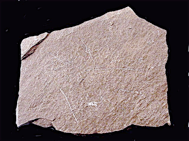

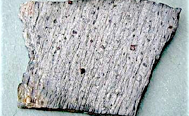

Mica layer surface along which the sandstone has split

Coal Measures sandstone - Northumberland

Millstone Grit - Derbyshire

Horsham stone - Sussex

Forest Marble - Gloucestershire

Chinese siltstone sold as roofing. Following immersion in sulphuric acid for one hour, it completely dissolved. A durable slate would be unaffected after 10 days.

Delamination (arrowed) in an un-metamorphosed stone after a few months on a roof. The fresh stone is black and the brown areas are stained by alkaline and pyrite inclusions.

Delamination in stone sold as slate but which is probably not metamorphosed.

SLATE True metamorphic slates can be split into thin strong sheets which are ideal for roofing. Geologically they can be very precisely defined by the degree of metamorphism which they have been subjected to and this in turn determines their physical properties especially strength or flexibility.

Unfortunately the term roofing slate has been debased by commercial interests and is now used to describe a whole host of products, natural or man-made, which are not slate.

In the UK natural roofing slates are produced in Wales, Cornwall and Cumbria. Formerly they were also produced in England, in Devon, Somerset, and Leicestershire; and extensively in Scotland and Ireland. Information on the former sources has been collected in:

-

- SCOTLAND

Historic Scotland, The Pattern of Scottish Roofing; Emerton G, and a number of geological publications by Joan Walsh. These are available from Historic Scotland

-

- IRELAND

The Heritage Council Ireland, Study of Irish Stone Roofs Part 2, Sarah Halpin

The Sources and Use of Roofing Slate in Nineteenth Century Ireland, Garrett O’Neill

-

- ENGLAND

Cumbria Amenity Trust, Slate from Honister, Alistair Cameron

Cumbria Amenity Trust, Slate from Coniston, Alistair Cameron

Blue Rock Publications, Honister Slate, Ian Tyler

James Milner (Barrow) Ltd Burlington Blue-Grey, R Stanley Geddes

Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, Regional Advice Note 2, Slating in South-west England, Terry Hughes (in prep)

-

- WALES

The publication of books about the Welsh slate industry has now reached a scale to rival the current production of Welsh roofing slates. The list is far too long to include here but good starting points are

Gwasg Carreg Gwalch, Llanrwst, A Gazetteer of the Welsh Slate Industry and Slate Quarrying in Wales both by Alun John Richards.

Many other slate and stone roofing publications are listed in the Stone Roofing Association’s bibliography

Shale

Mottled purple and green Welsh slates. Penrhyn quarry.

Irish slate, probably from Valencia quarry

West country slate. Trevillet quarry.

The thinly bedded calcareous siltstones of the Sandwick Fish Bed have been extensively quarried for roofing slates on Orkney.

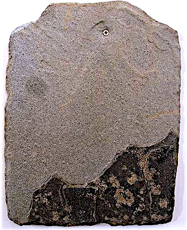

Igneous rocks can sometimes be split into thin layers but this is rare and they are seldom used for roofing. However some muds and silts of volcanic origin (the term used in the European roofing slate standard is volcanoclastic origin) have been metamorphosed and have slate characteristics. These include the Burlington Blue and Westmorland Green slates from the Lake District

Sedimentary rocks can be split into roofing thicknesses along sedimentary planes - the layers in which they were laid down - usually formed along natural discontinuities such as mica layers or representing a gradual change of grain size. Shales, mudstones and siltstones which are fine grained sedimentary rocks are often quarried for roofing on a local scale for example in Orkney. The roofing sandstones and limestones range from pure sandstones through calcareous sandstones to sandy limestones and limestones. Roofing limestones are most often obtained from the more sandy deposits.

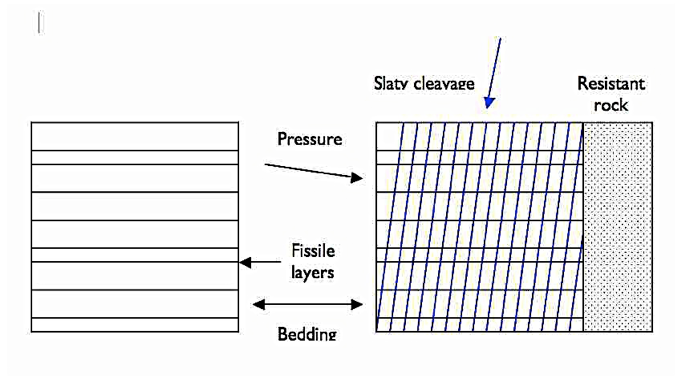

Metamorphic rocks are formed from sedimentary rocks such as shales by the action of pressure and / or heat typically during tectonic - mountain building - periods. This causes the minerals to change physically and chemically and to become realigned, in the rock fabric, along the line of least pressure, ie perpendicular to the pressure, producing cleavage planes almost always at an angle to the bedding of the original sediments. They are described as foliated. Phyllites and schists have undergone progressively greater degrees of heating and pressure and consequently split along layers of lamellar minerals such as micas, talc, chlorite, horneblende and graphite.

The splitting of sedimentary rocks is called fissility. In slates the splitting is called cleavage or more precisely, slaty cleavage. The quarrying term for splitting slates is riving (UK) and finished slates are said to be riven.

NB The terms mudstones or siltstone used in the UK are commonly known as shales in the USA. They are of equivalent grain size and metamorphic grade.

PHYLLITES AND SCHISTS These stones have been subject to higher grade metamorphism than true slates. However they are cleavable and suitable for roofing, many being very durable. Traditionally they have been called slates - Ballachulish ‘slate’ from Scotland is in fact a phyllite.

The old quarries at Cnocfergan on the Glenlivet Estate near Tomintoul produce roofing ‘slates’ from a coarse grained mica schist.

Schists have been imported to the UK from Norway, especially to Scotland and NE England. Often they were shaped.

The Cordon Hill stone slate in Shropshire is a very fine, laminated siliceous sandstone which has been altered by the effects of volcanism. It was formerly quarried for roofing and flooring

Ballachullish phyllite

Cnocfergan schist (image)

Easdale slate, Scotland, showing crenulations, cleavage and pyrite crystals on the cleavage plane.

Burlington Blue. Cumbria

Norwegian schist

I’m grateful to Dr Graham Lott for correcting the geology.